Influencing the Bradford Local Plan – Part 1

The Bradford Local Plan has been a long time coming. We took part in influencing the Core Strategy back in 2014-15, and it was eventually adopted in 2016. There should have followed a Sites & Policies Document to support the Core Strategy, but work on this stalled, and then Bradford embarked on a partial review of the Core Strategy in 2019, largely because the government figures for calculating housing need had changed and Bradford’s target needed to be reduced. This process again stalled, and now we have a whole new draft Local Plan out for consultation.

The early stages of a Plan are some of the most important in terms of community influence, because it’s called a Preferred Options consultation (or Regulation 18, in the technical parlance). This means that you can still suggest alternative options for what the overall strategy should be, as well as the site allocations that could follow from it. Later on in the process, there is much less room for manoeuvre.

So what has changed since 2016 that we should be commenting on?

Firstly, the overall housing target remains lower, at 1,700 per year, although the government has now also introduced a 35% uplift for large urban centres. This could push the housing figure back up to around 2,300 per year, but Bradford Council is keen that the additional homes should go into Bradford city itself, rather than being added on to the general housing target for the district – where it would tend to create pressure for additional greenfield and Green Belt sites.

Secondly, Bradford has declared a Climate Emergency, and West Yorkshire has published an important report, West Yorkshire Emissions Reductions Pathways. Taken together, these mean that by 2038 – the end of the period for this new Local Plan, Bradford should be at net zero carbon, and we know that to achieve this they need to achieve some huge transformations, such as a 20% reduction in car mileage. Bearing in mind that big picture measures like the West Yorkshire mass transit system, and the large-scale take-up of electric vehicles, won’t really have a big impact on emissions until after 2038, then Bradford has a lot of work to do to tackle emissions through other means before then, and achieving major reductions in traffic is a big part of that.

Thirdly, national planning policy has been updated and takes a much stronger line on ‘making effective use of land’. This actually means ensuring that available, suitable brownfield land is being prioritised, and that development densities are being increased. That should result in less land being needed overall, less pressure to release land from the Green Belt, and also more compact, walkable neighbourhoods where people are less dependent on cars.

What’s CPRE’s position?

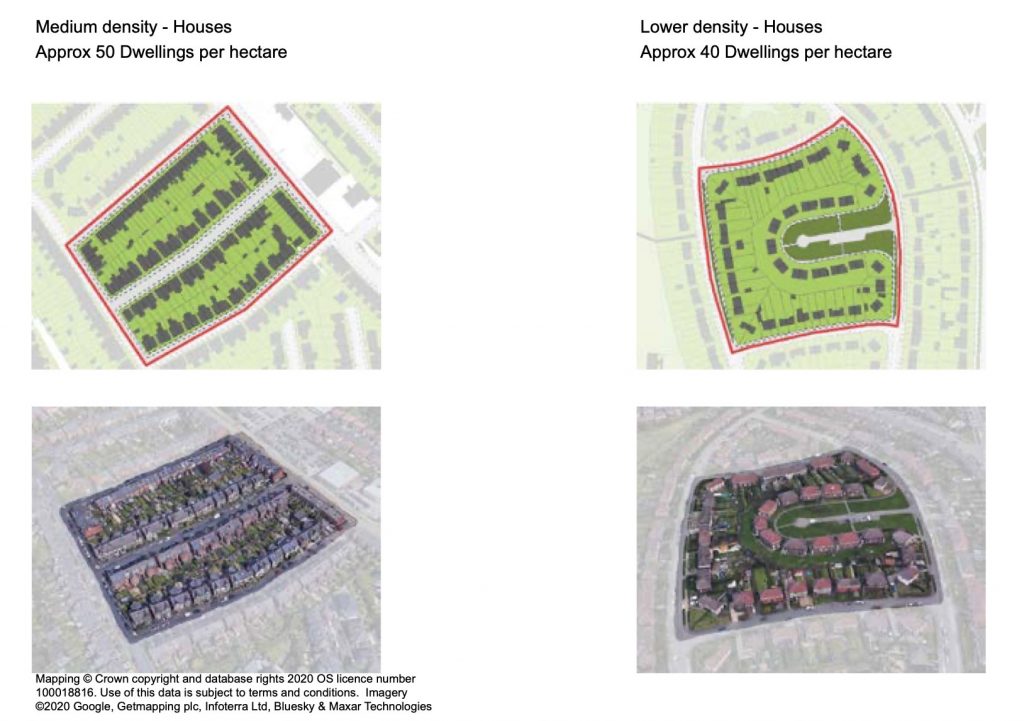

As ever, we want to see pressure on greenfield and Green Belt sites minimised, and also to ensure green spaces within urban areas are protected. Sometimes there’s a tension between these two goals, but if new development is built at the right density in the right places, it should be possible to get the balance right. The Bradford Plan proposes a minimum general density of 30 dwellings per hectare (dpha), but a minimum of 50dpha in highly accessible locations. This begs the question, of course: if you want to reduce car dependence and tackle carbon emissions, should you be building anywhere that isn’t accessible? We think the answer is no – which also means we shouldn’t be seeing new development below 50dpha (if you want to know what 50dpha looks like, there’s a good diagram from the emerging Sheffield Local Plan which we’ve reproduced here: it’s really like most urban streets built before about 1950).

We also want all Local Plans to make serious commitments on climate action. In short, that means all new development should produce reductions in carbon emissions, a genuine shift from car travel to walking and cycling, improvements for biodiversity and green space, reductions in flood risk, and measures for restoring tree cover, soils and peat bogs. Again, national policy is – in theory – on our side, requiring planning to “shape places in ways that achieve radical reductions in greenhouse gas emissions” (National Planning Policy Framework, para 148), but the Government is also famously fixated on numbers of homes being built – and this often seems to take precedence. We’re deeply concerned that building for numbers without building in climate action is a recipe for problems, and we also believe it is not actually legal, since local authorities have legal duties under the Climate Change Act 2008, and need to be doing everything they possibly can to fulfil those duties.

There are also concerns about how planning decisions seem to ignore or marginalise the needs of women, children and some people with disabilities. Women’s safety has been in the news recently, though in fact the issue is much wider than that: people’s perceptions of the places they live and work in, their exposure to air pollution and other hazards, and their personal safety when travelling around, really do affect strategic issues like reducing car dependence and encouraging children to walk to school, for example. Planning must play its part in addressing these issues.

And how does the Plan stack up against these expectations?

Part Two will be looking in more detail at the answer to this question and also explores our approach to this consultation.