‘Don’t start from here’: The saga of Leeds Green Belt

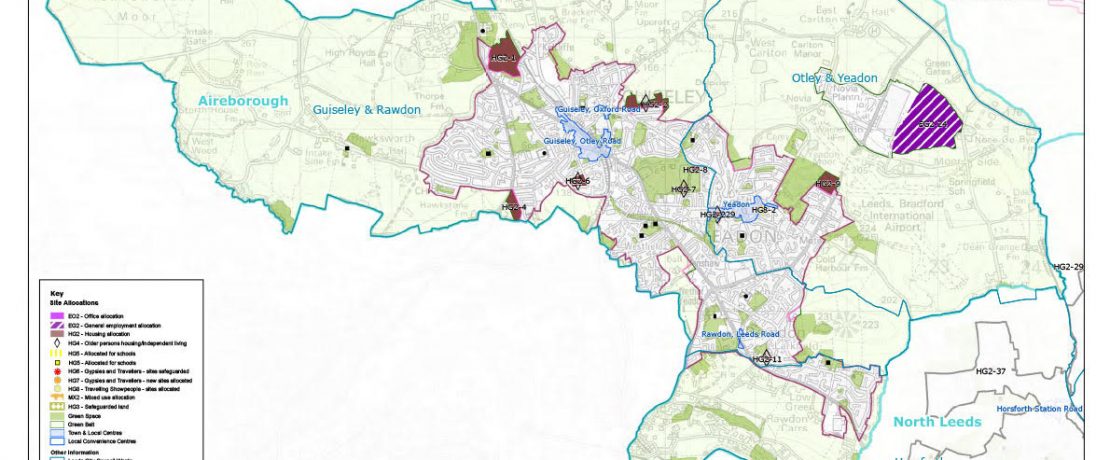

Aireborough Neighbourhood Development Forum (ANDF) has won a very interesting legal challenge to the Leeds Site Allocations Plan (SAP). Jennifer Kirkby from ANDF explained the background to the case in her article ‘How can local communities shape the future of their green belts?’

High Court judgments are not the most gripping of reads, but we need to work out what has actually happened. The following post tries to untangle the threads of the process.

An ANDF timeline of events is available here to view or download.

In January, a High Court Judgement established the right for the ANDF to bring this claim

And after a hearing in February, on the 8th of June 2020, the judgement was issued about the lawfulness of the Leeds City Council Site Allocations Plan.

Leeds City Council has issued a statement on the judgement.

The Challenge

ANDF challenged the SAP on seven grounds. The judge, Mrs Justice Lieven, accepted five of those grounds, but on two of them determined that they did not affect the outcome. Three of the grounds did make a difference, which means that errors of law were made in the process by which the SAP was adopted. Leeds City Council therefore has to come up with a solution. It’s too soon to tell what that solution might be, but at the very least it seems likely that a number of Green Belt sites in Leeds will not be built on before 2023, as originally designated in the SAP.

The Background:

CPRE worked to influence the Leeds Plan throughout a long, tortuous process. The ‘Development Plan’ is a technical term in planning referring to a suite of documents which combine to produce a statutory basis for establishing how much development goes where, and what policy criteria apply to that development. In this story, the crucial documents are the Core Strategy (adopted in 2014) and the Site Allocations Plan (adopted in 2019).

It’s also important to know that Development Plans normally plan for a period of around 15 years, but reviewing a Plan normally takes about 5 years to do. Leeds would have begun work on the Core Strategy around 2009. This is significant, because in 2012 the government published the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF), which heralded a major push to boost the supply of new housing and created a focus on Localism in the planning process.

The housing supply targets of 70k that Leeds City Council (LCC) planned for had been originally identified in the previous Regional Spatial Strategy (RSS) for West Yorkshire. When, in 2010, LCC commissioned a modelling for housing need, the scenarios ranged from 90k down to around 40k. Leeds City Council chose to stick with the aspirational housing figure of 70k, even when the 2011 census data showed that projections for populations were lower than the RSS had used.

The plan-making team at Leeds City Council then had to try to fit these huge numbers for housing into the plan, and this meant more land. The owners of potentially lucrative greenfield sites in the Leeds Green Belt were very keen to help with that supply problem.

It was painfully obvious that these new housing numbers were too high, but Leeds City Council did not choose to undertake a review of the figures. As a result, the Core Strategy came into force in 2014 with a housing target of 66,000 new homes. This meant building at more than double the rate that had been achieved any time in the previous 20 years.

This ‘aspirational’ housing figure created an artificial shortage of land. This shortage was used as a justification for the exceptional circumstances required for reviewing Green Belt boundaries and the release of land. At that time, CPRE argued that because the required build rate to meet the housing target was wildly unrealistic, the effect of releasing land from Green Belt would not be to boost housing supply but simply to move supply on to the edges of the city. This would be at the expense of countryside and at the expense of regenerating inner urban neighbourhoods.

We lost this battle.

It was at this time, between 2010 and 2014, that Leeds City Council made the fatal error that ultimately led to last week’s High Court judgment against them. The Core Strategy divided Leeds into 11 ‘Housing Market Character Areas’ (HMCAs), but the distribution of new housing numbers was only determined by land availability and the drafted spatial strategy.

The amount and type of housing need in each HMCA was not considered. In some HMCAs, much of the ‘available’ land was in fact in the Green Belt, and would by law require a Green Belt review to make it available. Despite this, the Core Strategy was adopted by Leeds City Council. It is the view of CPRE, ANDF and many others that the Core Strategy was adopted on the presumption that enough Green Belt land could be released. No connection was ever made between whether a particular HMCA, such as Aireborough, needed a given amount of development, and whether the exceptional circumstances for Green Belt change existed. The only measure of exceptional circumstances was made at the Leeds-wide level, and it just happened that Aireborough had some Green Belt land in it that might fit the bill.

There had already been a substantial amount of new house building on old mill sites and other greenfields in Aireborough. The feeling that Aireborough had already shouldered a considerable amount of weight for housing requirement, and concerns around pressures on existing infrastructure, led to the formation of the ANDF. They hoped to involve the local community in developing a Neighbourhood Plan when the creation of the NPPF and the Localism Bill made this possible.

Fast-forward to 2017. Leeds had spent 4 years working up a Site Allocations Plan (SAP) based on finding enough sites for 66,000 homes and sent it to the Planning Inspectorate for Examination.

During this time, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) population forecasts for the area had been falling. At the same time, Leeds City Council had fallen behind in the delivery of the aspirational housing targets, and had lost a number of appeals relating to the 5 Year Housing Supply. The housing target was, according to law, out of date.

In November 2017, Leeds City Council launched a review of housing targets while the SAP was still waiting for examination with the Planning Inspectorate. But just as the Local Plan hearings were about to start the Government launched a new housing need methodology – this showed that the Leeds housing need was likely only 42,000.

This new figure undermined the exceptional circumstances for the release of Green Belt land for development, it also triggered a partial review of the Core Strategy, but the SAP was already on its way to Public Examination and was a legal requirement for the site allocations of the out of date Core Strategy.

It was, in essence, a mess.

Are you still following this? Fetch a drink and come back refreshed.

The High Court Judgement:

Mrs Justice Lieven found that:

- Because the 66,000 target was already being reviewed downwards, and

- Because the Inspectors examining the SAP had not noticed two errors in calculating supply including an error in the way windfall (i.e. unexpected) sites had been counted.

The correct, up-to-date figure for housing land requirement at the time the SAP was adopted could have been met without recourse to any Green Belt sites.

Therefore, on a Leeds-wide basis, the case for exceptional circumstances to take land from the Green Belt had completely evaporated.

Then came the second part of the error. Leeds City Council argued that the distribution to each HMCA was locked in by the Core Strategy, and that it should simply be reduced in proportion for each on a fair shares basis. This was not the spatial strategy in the CS. It meant that in HMCAs where most of the available sites were in the Green Belt, these sites would still be needed even if the total number was reduced. That is, Leeds City Council argued that there were locally exceptional circumstances. But this was wrong because, as you will recall, local housing need had not influenced the initial distribution.

Mrs Justice Lieven found that the SAP Inspectors might have made a planning judgement that, even though local housing need hadn’t originally informed the distribution, there was nevertheless a need for development in Aireborough that couldn’t be met without the Green Belt sites, and that exceptional circumstances did exist. But the Inspectors didn’t make that judgement.

They had accepted there were exceptional circumstances for GB release, whilst also saying that in the period up to 2023, which was the time frame for the ‘short-term’ SAP, there was no need to refer to the HMCA targets. They did not then explain why they had then accepted the proportionate distribution figures across HMCAs. This was incorrect in law, because if there is no overall need for Green Belt release at the Leeds-wide level, then a proportionate share of nothing is, of course, nothing.

As for what happens next, we must wait and see. If Leeds can show that they still have sufficient supply of housing land for the amount of homes now being planned for over the next 5 to 7 years, then the outcome may be quite subdued. The SAP can be reviewed to put the Green Belt boundaries back to their previous position and adopt the updated, smaller housing figure. But a number of developers will be circling, determined to show that there are now insufficient sites available, and we may see a new wave of aggressive planning applications. Either way, it shows that planning is far from dull, and it’s a striking case study of what a determined Neighbourhood Forum can achieve with the right tools and knowledge to challenge the system.